Castles in the Cloud

- 7 minsI have a confession to make….when I started in Team Platform at YoungCapital, I had no idea what the team was actually responsible for and what they were doing. Little did I know I was about to rocket to a new world in The Cloud… When I joined the team, the company had just decided to move their projects from AWS (Amazon) to GCP (Google Cloud Platform) and I was part of the “movement”. In this post I’ll explore some of the architectural and implementation designs we made while building our infrastructure. It might help clear some fogginess for non-DevOps engineers.

Tools

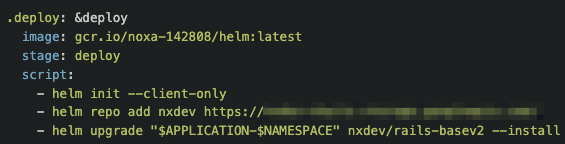

Here’s a quick run on some of the tools we use at YoungCapital. All our applications run in Docker containers and we use Kubernetes for our container deployment and Helm as a package manager for Kubernetes. We use a Helm template for all our deployments so our developers won’t have to write an insane amount of YAML. We use Terraform (Infrastructure as Code) for building, changing, and managing the infrastructure that your apps need in a safe, repeatable way.

Where is my application?

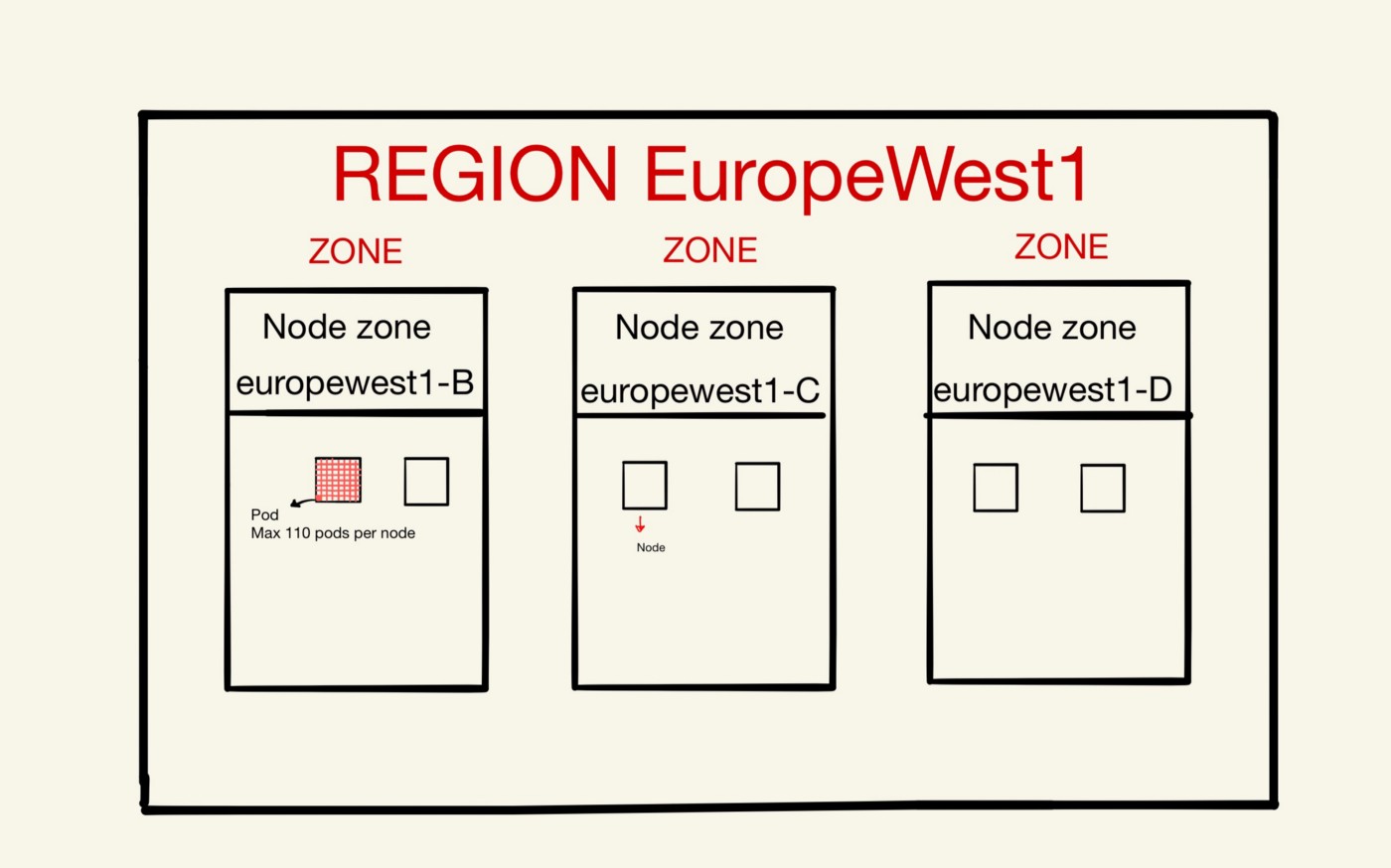

We currently have several Kubernetes clusters running in GCP. These clusters, like production and staging, are run in a region which is a location called Europe-West1. Now, let’s break this down till we find where our applications run in the cloud.

This region is split into zones (in parts of the region). Some data is valuable and since we don’t want to lose any of it, we placed machines in different zones within the region. Having a multiple-zone cluster reduces the impact of zone failures.

If one or more (but not all) zones in a region experience an outage, the cluster’s control plane (master) remains accessible as long as one replica of the control plane available. During cluster maintenance such as a cluster upgrade, only one replica of the control plane is unavailable at a time, and the cluster is still operational.

For production we have 3 zones running. These zones contain 6 nodes, which are (physical) worker machines in Kubernetes.

In most common Kubernetes deployments, nodes in clusters are not part of the public internet. Each node contains a maximum of 110 pods. A pod is a group of one or more application containers with shared storage/network. Containers within a Pod share an IP address and port space, and can find each other via localhost. It’s in these pods where our applications run. The application containers are tightly coupled and executed from the same machine.

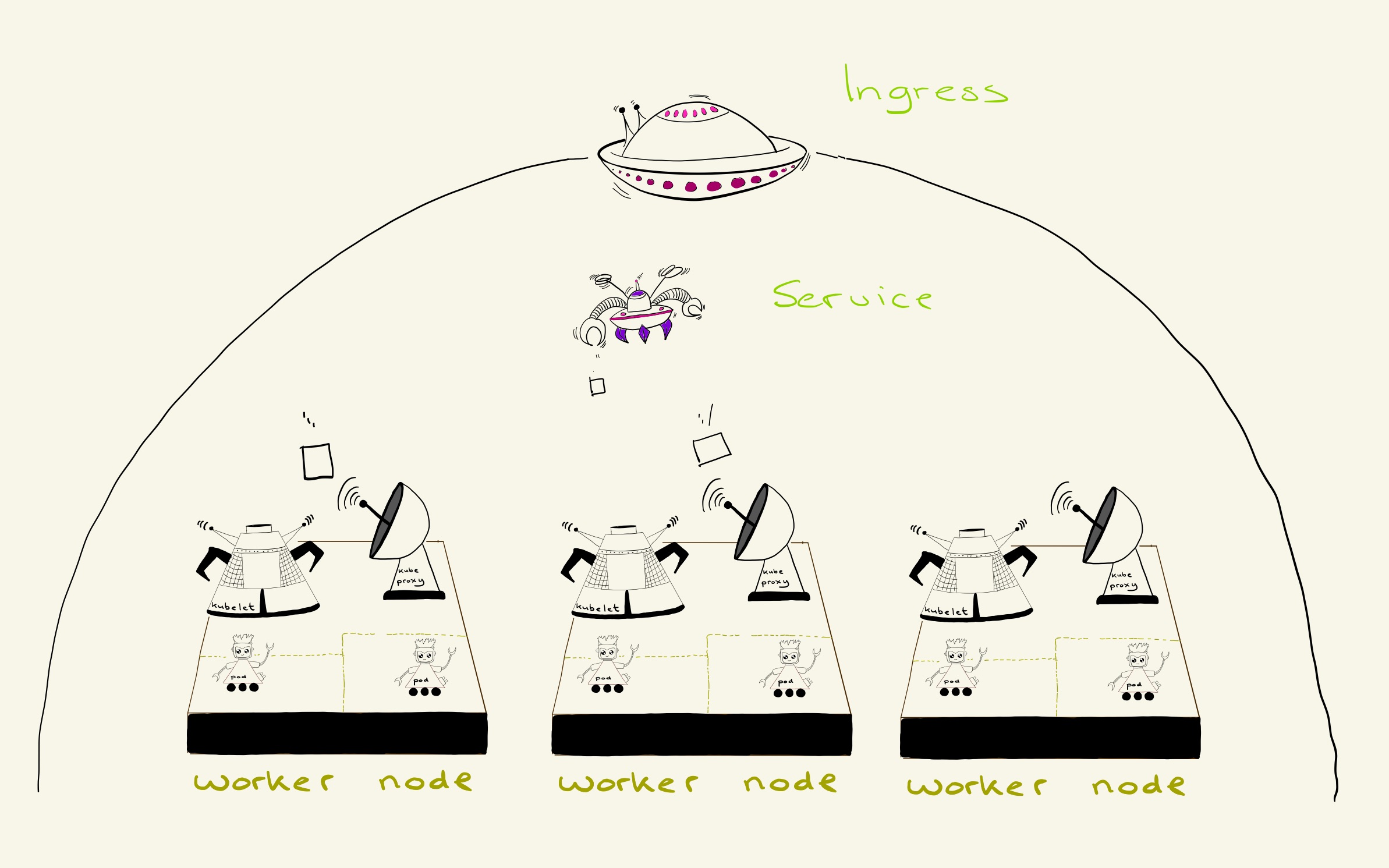

Services & Ingress

In order for other applications to ‘find’ your application, we use “services”.

We use the concept of a service to enable service discovery and it also provides internal or external load balancing for your application. So if there are multiple copies of your application running, the service will automatically detect all running replicas and divide all requests equally among the replicas. -Karst Hammer (sr. software engineer at YoungCapital)

In Kubernetes, an Ingress is an object that allows access to the Kubernetes services from outside the cluster. Every application that runs within our production cluster has an ingress in which we configure the URL of the app and the service name of the app. When traffic comes in, the Google load balancer sends the requests to an Ingress controller which collects all the Ingresses we have in our production environment. The Ingress controller finds the correct service to send the requests to and the service (also working as a load balancer) splits the loads to the pods where the project lives.

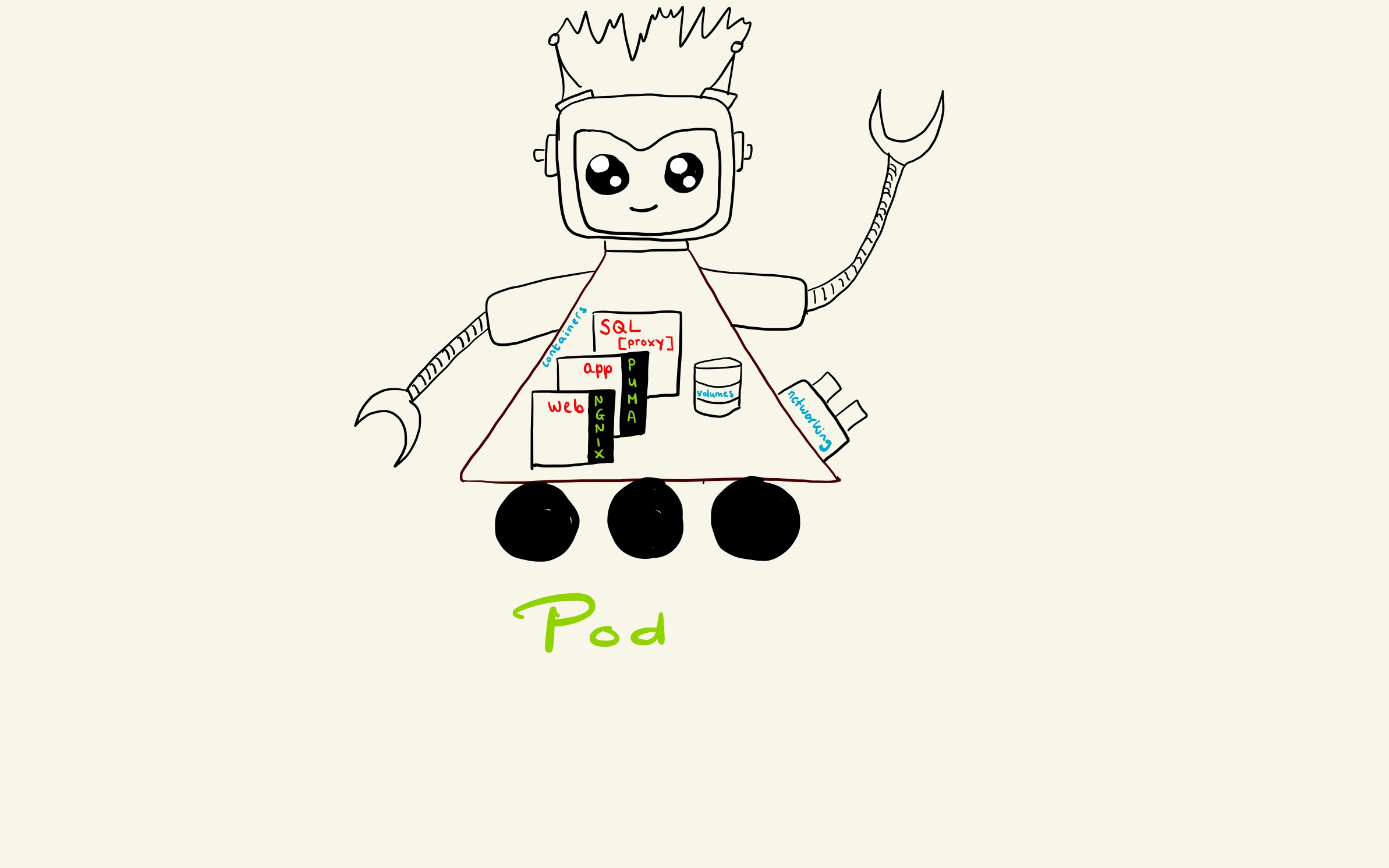

The Web and App container

A project in the pod runs in 3 containers: web, app and (optionally) SQL proxy (fig 2). The web container of the app holds all the static and public files like application CSS and/or JS files. The assets of the application can be found in the web part of the project which is being served by Nginx. Nginx (pronounced “engine-x”) is an open source reverse proxy server for HTTP, HTTPS, SMTP, POP3, and IMAP protocols, as well as a load balancer, HTTP cache, and a web server (origin server). In this case we use it as a web server to serve requests for assets extremely fast. The second container holds the app part of your project. All the business logic can be found there and is served by a Puma web server. So how do the assets of the app container get in the web container, since the web container is the same for all applications we deploy? Kubernetes uses volumes for this.

A Kubernetes volume is a directory defined in a given Pod, that contains data accessible to containers but it can only be mounted into a single container. So, in order for the web container to access the app container data, we use an ‘initContainer’ that copies the assets from the web container into the volume used by Nginx and after that Nginx can serve them. You can see how this is configured in the GitLab-CI file of the project where the deploy is handled by Helm. The deploy points to the Helm charts where we have configured the Helm templates. In the Helm template we mount the assets of the app container to the web container using Docker mount.

Google Cloud SQL proxy

Many Google Cloud resources can have both internal IP addresses and external IP addresses. Instances use these addresses to communicate with other Google Cloud resources and external systems. Google Cloud offers three options for hosting databases:

- External IP (IP Whitelist)

- Google Cloud SQL Proxy

- Internal IP (no IP Whitelist)

A static external IP is used when an instance requires a fixed IP address that does not change. You can assign a specific internal IP address when you create a VM instance, or you can reserve a static internal IP address for your project and assign that address to your resources. YoungCapital uses the second option, the Google Cloud SQL Proxy, to connect applications to databases which are not hosted within the same cluster your application is running on.

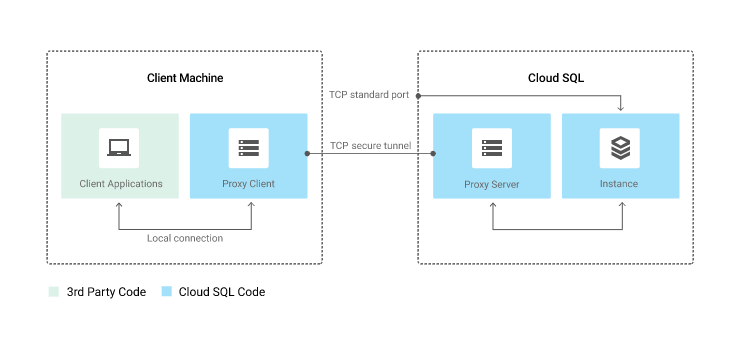

This setup looks a bit like a VPN but it’s not quite the same. The Cloud SQL Proxy works by having a local client, called the proxy, running in the local environment. Your application communicates with the proxy with the standard database protocol used by your database. The proxy uses a secure tunnel to communicate with its companion process running on the server. The following diagram shows how the proxy connects to Cloud SQL:

To access the data, we put tokens, ssh keys and certificates in Kubernetes “secret” objects. Adding this information in a secret object allows for more control over how it is used, and reduces the risk of accidental exposure. To use a secret, a pod needs to reference the secret. Team Platform uses Terraform (Infrastructure as Code) to manage all the secrets.

This is a part of the work we do in Team Platform: build, deploy, monitor the platform components and the platform infrastructure. But it’s not just working in The Cloud though. The Platform team also provides, operates and designs services like security (i.e. GDPR), storage (ElasticSearch, Redis) and identity management (Authentication, Authorization).

We also help other development teams with designing their infrastructure (technical discoveries) but they are responsible for their own projects: You build it, you run it.